Reproducing the myth of "harmonious" village

The dangerous myth of "harmonious" rural village is hegemonic in Indonesia. I argue that many in the agrarian and rural scholar-activist circles can be complicit in reproducing such myth.

Geger Riyanto wrote an interesting article that addresses some issues that I’ve been thinking about for a long time regarding the public discourse on Indonesian rural and agrarian political economy. In the article, he described the disconnect between the “sensibility” of anthropologists in producing respectful and representative realities of the peoples and communities they studied with the “social representations” that Indonesian anthropologists actually produced in the public discourse.

Riyanto explained that this disconnection was rooted in the structural and institutional constraints where anthropological works and research are done in Indonesia. Similar to the problems that can be found in the Indonesian academic and research ecosystem more broadly, the field of anthropological research is also characterised by a lack of academic job opportunities and scarce public funding. As a result, Indonesian anthropologists are often dependent on government agencies, private donors, or NGOs for supports and resources in research. But because these organisations tend to have their own pre-determined goals and research framework, the consequence is that:

Anthropology-trained individuals are constrained to prevailing representations produced by the institutions they work with. To address the issue of deforestation [for example] they must either work with poverty alleviation programs or conservation campaigns. This necessitates them to either reproduce the representation of forest communities as the impoverished root of forest loss or as the timeless stronghold of ecological sustainability, all while acknowledging other realities of the people they represent. (p. 28)

What I found interesting from Riyanto’s observation is that such disconnect between “social realities” and “social representations” also exists in the context of agrarian and rural political economy. As Ben White noted, the Indonesian village or rural society is commonly perceived as:

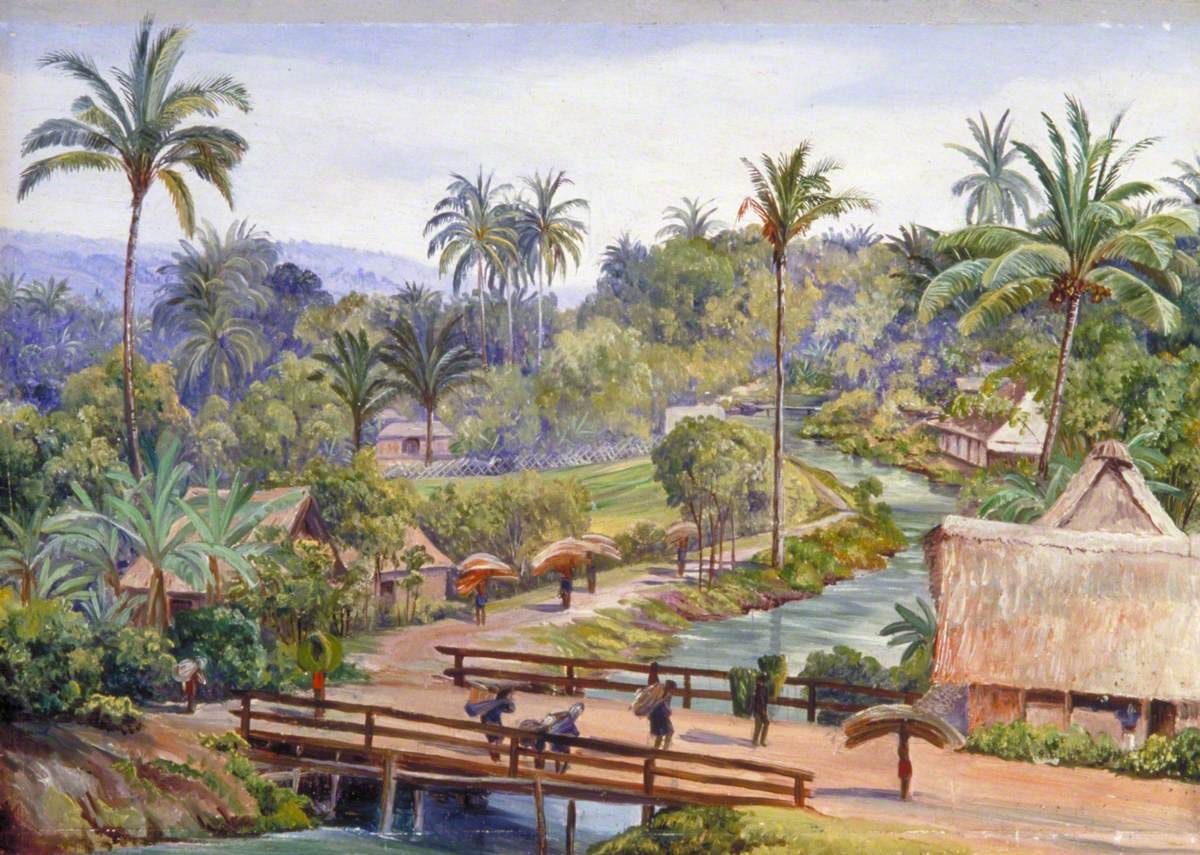

idylls of tranquility, consisting of a homogeneous and classless ‘peasantry’ practicing ‘subsistence farming’ while being insulated from the cash economy. These villagers work together without conflict, guided by shared values of gotong royong (working together), kekeluargaan (family spirit) and rukun (harmony).

However, as he argued, this widespread notion of an “egalitarian” and “harmonious” rural village is largely a myth. Many research have shown that the rural villages or societies in Indonesia are defined by class differentiation and inequality, rooted mainly in unequal ownership and control over land but also other economic resources. A context where relations of exploitation and subordination of the rural labouring classes by the village’s ruling classes, or what Lenin called “masters of the countryside”, are hegemonic.

Personally, I am not particularly interested in these issues. But I have first hand experience of how this disconnection does not just result in misleading discourse but can actually produce harmful consequences.

Reproducing the myth

In 2020, I was invited as a presenter for a “Sekolah Agraria” (Agrarian Research & Advocacy School) organised by a sizable student activist community in Yogyakarta to teach some introductory materials on “social analysis”. Originally, I wasn’t supposed to be the presenter, for the obvious reason that I am not experienced or knowledgeable at all on rural and agrarian research. A friend of mine was previously invited as the presenter but, because he can’t attend, he sent my name to them as his replacement instead.

During my presentation, we were discussing social structure. Because this is related to agrarian research, I asked the students whether they know or have read Henry Bernstein’s Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Only a handful of them raised their hand, which was fine because I didn't expect them to know the book. So instead I asked them again whether they were already familiar with the notion of class inequality in rural Indonesia. It was a rhetorical question, but I was horrified when I saw a look of confusion among them. After further questioning it turned out that most of the students are not at all familiar with the notion of rural class inequality! In a purportedly agrarian research and advocacy school!

This was particularly strange since I also looked at the schedule and saw that my session was placed at the last day of the four-day sessions. The important materials on “agrarian issues” and “agrarian social movements” in Indonesia were already covered in the previous sessions, with the name of a renowned agrarian scholar-activist (from an equally prominent agrarian research and advocacy organisation) listed as the presenter. As a result, despite neither having the experience nor expertise on agrarian and rural research, I ended up providing them with some materials on the basics of class analysis of rural villages using whatever knowledge I had from reading academic papers and partaking in a few public discussions on the topic.

After my session was finished, I asked the organisers whether in the previous sessions they were taught similar materials that I gave on rural social inequality and they answered frankly with a “no”. When I asked them what or where they were planning to do their research or advocacy, they answered “oh it's the villages where there are conflicts over land grabbing (perampasan tanah).”

My anecdote is illustrative to the extent that the myth of a “harmonious” village is hegemonic. Even within the nominally-leftist space, such as among student movements or “progressive” academics, there is a widespread belief that agrarian conflicts only exist when there are open and visible confrontation, mainly between “peasants” (petani) or “the people” (rakyat) against larger enemies such as the state, corporations, or the ruling class (kelas penguasa). Meanwhile, the less overt, and invisible, conflicts occurring daily within “the people” themselves—between farm workers (buruh tani) and their rural employers (majikan) over agricultural wages, between tenant farmers (petani penggarap) or sharecroppers against their landlords (tuan tanah) over rent arrangements or the village’s land distribution, between the rural poor and labouring classes against their rural dominant classes over the village’s economic resources and public policies—are either ignored or treated as non-existent.

Furthermore, many senior scholars and activists can often be overly antagonistic to outsider or young researchers that openly take a more critical view on rural life. I recalled when Muchtar Habibi once delivered a public lecture on agrarian transition where he argued of the need for more research that "expose rural class inequality" so the public can form "new imagination" about the villages which challenge the pervasive "harmonious” village myth. After hearing Habibi’s remark, a senior agrarian scholar/activist who sat near me muttered a snide comment "marxis kok ngomong imajinasi?” (why would a marxist talk about “imagination”?). In another case, a senior agrarian activist wrote a scathing and unjustified review of a book written by a young researcher, W. D. Yistiarani, based on her research on agrarian class dynamics of a village that was once the site of state-led land grabbing to build an airport in Yogyakarta. Rather than engaging with the merits of the findings or analysis, the review spent an inordinate amount of words using ad hominem and questioning the credibility of the author while elevating his own position as a senior activist with the authoritative experience, knowledge, and significant contributions on agrarian social movements.

These anecdotes led me to harbour a suspicion towards agrarian or rural scholar-activist circles in Indonesia. I found it perverse that a renowned and senior figure of the field failed to teach crucial knowledge of rural class inequality to a bunch of students in an event organised specifically as an agrarian research and advocacy school. If this is not the right place to expose the myth, where else? It’s not like these scholars also spent time writing or speaking to the public challenging the dominant myth. It’s easy to believe that those scholars and activists are being dishonest: they know about rural class inequality, but for one reason or another choose not to publicly share the knowledge.

Furthermore, the overly dismissive response by senior scholars and activists toward those who took a more critical view on rural life rather validates my own bias that the myth is the “best kept secret” of agrarian or rural research and advocacy circles. Again, studies on internal class inequality and exploitation in rural Indonesia is nothing new. It stretches back to research on the socioeconomic impact of the Green Revolution in rural areas under the New Order to the infamous research on the “Seven Village Devils” conducted by the Communist Party of Indonesia and the Indonesian Farmers’ Front (Barisan Tani Indonesia) in the 1960s. Almost as if there is an interest for any critique or challenge to the myth to be nipped in the bud.

Constraints to knowledge production helps reproduce the myth?

However, reading Riyanto’s article and productive discussion with a few active rural scholar-activists made me reconsider my own view. Instead, I believe that the issue is better understood in terms of structural and institutional constraints for agrarian or rural political economy research in Indonesia.

Like their anthropologist comrades, agrarian or rural researchers face similar constraints in terms of resources or institutional support. They are highly dependent on institutions like research and advocacy NGOs (whether focusing on rural, agrarian, or “indigenous” issues) for their research. However, many of the NGOs have a strong institutional presence in the local communities or areas that researchers want to investigate. Not only that, the rural and agrarian scholar-activist circles are small and very close-knitted, where pretty much anyone almost knows everyone, and where further institutional or network support can sometimes depend on forging personal networks with key figures within the circles.

Many NGOs and senior researchers or activists serve as powerful “gatekeepers” that can influence access, knowledge, and institutional support to outside or young researchers looking to carve a place in agrarian and rural research. To compound matters even worse, many of the NGOs and scholar-activists themselves are also reliant on government agencies, donors, or international NGOs for funding, each with their own strict narratives or frameworks to approach rural or agrarian issues.

Because of this, researchers have incentives not to risk losing such crucial resources or support. As Riyanto has argued, regardless of the “social realities” that they might find in their field research, researchers can be compelled to produce particular “social representations” that better fit the views of such gatekeepers but might not accord with their own beliefs or theoretical frameworks. Even when speaking or writing for the public, they might be more careful not to “stray” far from the established or popular narratives about rural society, leaving the myth of the “harmonious” village unchallenged.

The virtual absence of counter-narratives or alternative analysis on rural inequality ensures that the myth is perpetuated in the public discourse, influencing not just political activism but also social research and policymaking. As long as the myth remains dominant, the emancipation of the rural poor and labouring classes from the relations of exploitation, subordination, and marginalisation that they experience in their day-to-day life by their village’s better-offs will have to be postponed.

Absolutely wonderful read. I agree with the idea that "the myth of a “harmonious” village is hegemonic." Even though I have limited experiences going to villages, and for short times, I too did encounter how much these rural inequalities affect the villagers, especially for those smaller farmers who had to contend with the double whammy of fluctuating prices and the changing climate (the main topic of some of my studies there). Sometimes I feel that Multatuli's ironic satire of Dutch society that "doesn't believe fertile Java could ever have a famine" could still be applied to this day, as society gets more out of touch with the conditions in the rural areas. The gap, I feel, is ever-widening. The myth of a "harmonious" village, still hegemonic, certainly doesn't help to bridge the gap.

I have no idea if you've read David Bourchier's book, "Illiberal Democracy in Indonesia: The ideology of the family-state" but it agrees a lot with your conclusion that "the harmonious desa," along with other concepts like "kekeluargaan" and "gotong-royong," could and has been used for anti-democratic ends, as in the New Order era, and the fact that there have yet to be any other conceptions of those terms still shows the lingering hegemony of New Order era discourse. This, unfortunately, is the problem—something I hope we can get rid of one day.

Overall, you captured the problem well and poured it into a good read. Kudos!