Varieties of collective bargaining systems and why they matters

There are different ways of doing collective bargaining between unions and employers. Studies show the key role of centralised and coordinated bargaining in creating a more inclusive labour market.

In a typical employment relation, an individual worker would negotiate their wages or compensation with their employer usually during the hiring process or after years of working. This is known as individual bargaining. But workers can also organise together and negotiate with their employer as a collective. This is known as collective bargaining. Under a common collective bargaining process, workers in a company organise into a labour union and have the union negotiate a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with management or employer that set the terms of work in the companies—anything from wages, working conditions and hours, sick leave, vacation, and employment benefits.

But this is far from the only way for doing collective bargaining. Many countries have adopted different ways of organising their labour market and collective bargaining institutions. For example, a 2019 report by the OECD, Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work, and a subsequent academic paper by one of its co-authors examines the regulatory details and mechanisms of collective bargaining institutions across OECD countries.1 The report and paper identifies 5 distinct collective bargaining systems, each with its own institutional specificities and arrangements. In addition, far from being merely cosmetics, the report and paper also shows that different collective bargaining systems can have important labour market outcomes.

Dimensions of collective bargaining system

In their paper, “Collective Bargaining, Unions, and the Wage Structure: An International Perspective”, the labour economists Simon Jäger, Suresh Naidu, and Benjamin Schoefer provide an excellent and detailed explanation about different models of collective bargaining systems in both the developed and developing economies. They argue that collective bargaining systems across countries can vary according to three key dimensions: coverage, centralisation, and coordination.

Coverage

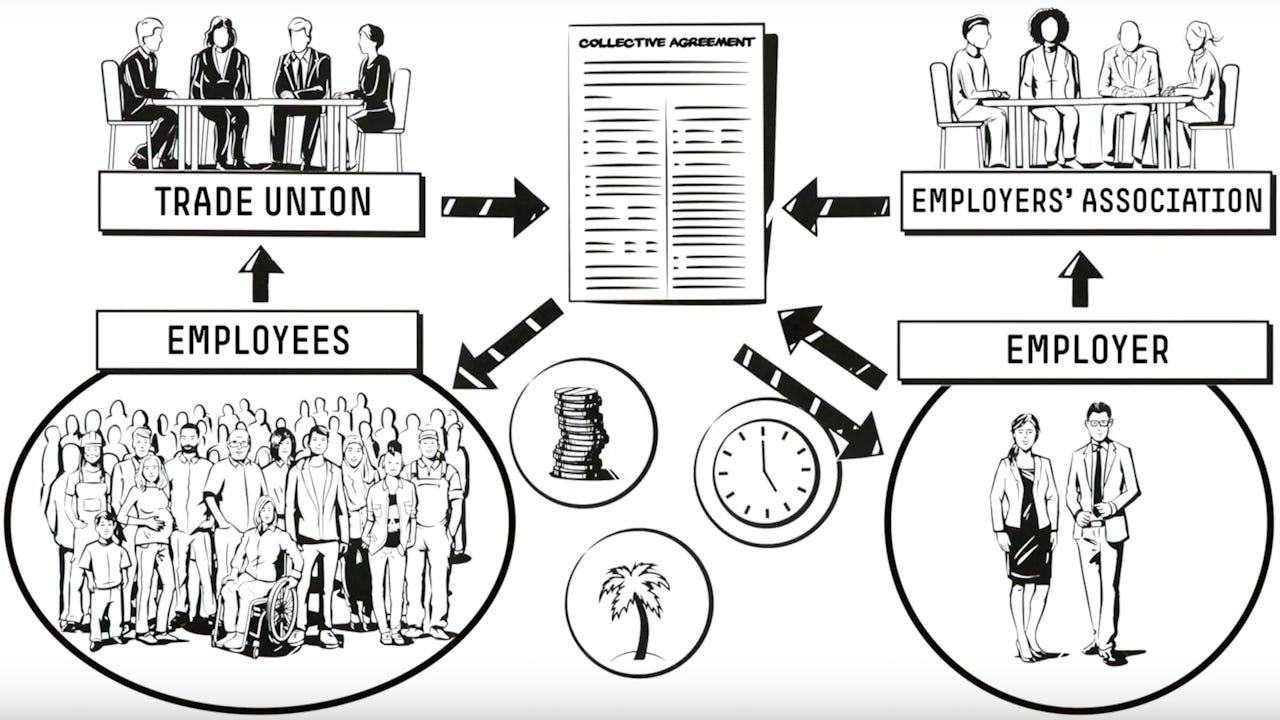

Coverage signifies the share of workers who are members of a labour union, e.g. union density, and the share of workers that are covered by CBA. From Figure 1 we can see at least three patterns in the relationship between the share of workers covered by CBA and union density between countries:

Countries with low union density and CBA coverage (e.g. US, UK, New Zealand, and Canada)

Countries with low to moderate union density but relatively high CBA coverage (e.g. France, Germany, Australia, Greece, Austria, Spain and Italy)

Countries with moderate to high union density and CBA coverage (e.g. Norway, Belgium, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland)

There are a few reasons for the variations between CBA coverage and union density. First, some countries (e.g. the Nordics and Continental Europe) have a history of strong organised labour movements and left-wing political parties which was reflected in their relatively higher union membership rate among workers and corporatist economic institutions—where labour unions have a more extensive role in policymaking and economic governance. Second, the variations can also be attributed to the different levels of centralisation in collective bargaining across countries, as will be explained below.

Centralisation

Centralisation highlights the level of which collective bargaining mainly takes place and CBAs are applied to.2 Across countries, unions and employers can conduct collective bargaining along three levels (see Figure 2):

Cross-sectoral or national-level bargaining (e.g. Finland, Belgium, France, Italy, Spain, and Iceland)

Sectoral or industry-level bargaining (e.g. Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands)

Firm- or enterprise-level bargaining (e.g. US, UK, New Zealand, Australia, and Canada)

Under a typical decentralised system, collective bargaining primarily takes place on a single firm or enterprise. In contrast, some countries have a centralised system where collective bargaining occurs on a sectoral or even national basis. In countries with sectoral bargaining, a labour union representing a specific sector or industry (e.g. manufacturing, mining, transportation, services, or the public sector) negotiates CBAs for that sector. Unions can also conduct cross-sectoral or national-level bargaining where they negotiate CBAs that would apply across sectors and industries.

Centralised collective bargaining systems also entail different degrees of flexibility for lower-level agreements. This entails the ability for lower-level CBAs to deviate from higher-level agreements, including the provision of “opt-out” from higher-level agreements or the application of “favourability principles” in which lower-level CBAs can only improve upon higher-level agreements.3 Some countries that have a highly centralised bargaining at the sectoral or national level such as France, Italy, or Finland provide a limited flexibility for lower-level agreements while countries that predominantly use sectoral bargaining such as Sweden, Germany, or the Netherlands provide a higher degree of flexibility.

Moreover, a centralised system can employ “mandatory” or “administrative” extensions that extend CBAs to cover all workers and firms in the sector where the agreement is applied for—regardless of whether they are unionised or not.4 CBA extensions can be legally enforced by the state (such as in France, Finland, Belgium, Italy, or Spain) or voluntarily by the union federations/confederations and employers’ associations as part of the collective agreement (such as in Sweden, Germany, and the Netherlands).

Accordingly, the degree of centralisation in collective bargaining and mandatory extensions of CBAs can explain some of the variations between union density and CBA coverage. In countries where collective bargaining are decentralised at firm-level, CBA coverage coincides with union membership so low union density results in equally low CBA coverage. Meanwhile countries such as France, Italy, or Spain can use centralised collective agreements and legal or state-enforced extensions of CBAs to cover workers and firms that are not unionised. Consequently, they have higher CBAs coverage despite their low union density.

Coordination

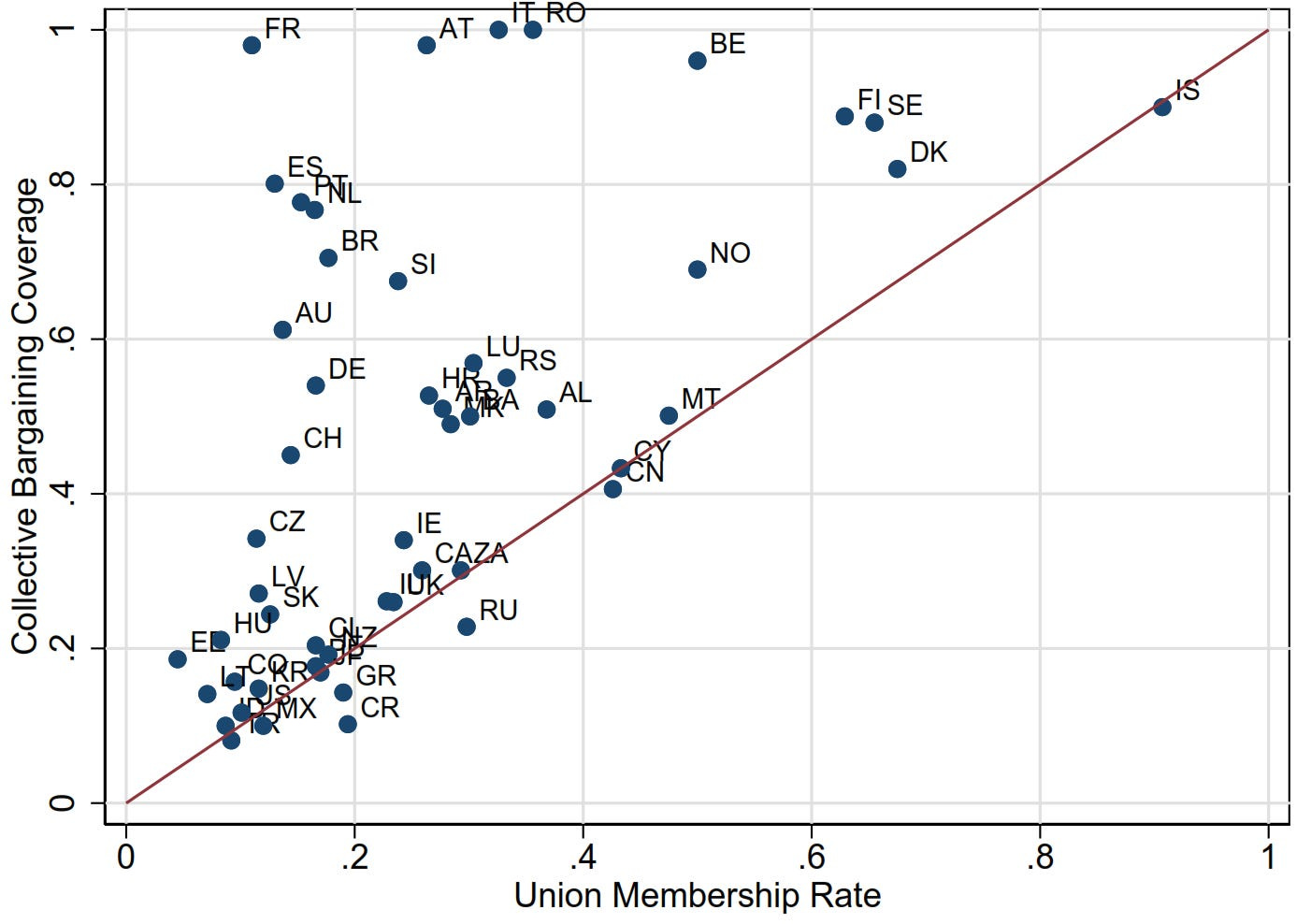

The final dimension is the degree of coordination in collective bargaining across firms and sectors (Figure 3). This signifies the degree in which unions and employers coordinate their collective bargaining according to the standards or guidelines set by higher-level agreements (vertical coordination) or by following the collective agreements set by firms or sectors within the same bargaining level (horizontal coordination). Some countries have a limited coordination in collective bargaining, where sectoral bargaining might take little into account collective agreements in other sectors, while in other countries collective bargaining across firms and sectors are highly coordinated with one another or even follow collective agreements set in other sectors.

According to the 2019 report by OECD5, coordination in collective bargaining can be achieved through three mechanisms:

Strict statutory control (or state imposed/induced): using rules set by higher-level collective agreements that must be followed by lower-level agreements or enforced by the state such as indexing wage to inflation/living cost, binding minimum wage or wage floor, and even accounting for “wage norms” across the economy.

Pattern bargaining: collective agreement in one sector, usually the export sector, sets the standards that other sectors can follow for their sectoral bargaining.

Inter- and intra-association guidelines: peak-level union and employer organisations set the collective bargaining frameworks, norms, or objectives that must be followed by lower-level collective agreements.

Coordination in collective bargaining is important because it enables both the unions and employers to internalise macroeconomic conditions in collective agreements.6 Unions often take into account macroeconomic indicators such as inflation, unemployment, and wage distribution during the collective bargaining processes—especially to achieve the goals of full employment and wage equality. On the one hand, they aim to ensure that improvements in wages and working conditions do not lead to significant unemployment and inflationary pressures as well as to maintain economic growth and the competitiveness of the export sector. Moreover, some unions use coordinated bargaining to ensure stable employment during economic downturns such as by moderating wage increases or reducing work hours. On the other hand, unions often take into account the overall wage distribution in the economy and aim to pursue “solidarity wage policy” by compressing wage inequalities between workers in different sectors, firms, and occupations. Thus, collective agreements often prioritise wage increase for workers with lower wages while moderating the wage rise for those with higher wages.

Different ways of organising collective bargaining system

Based on these dimensions, countries can have a very different collective bargaining system. Even if they are similar along one dimension—whether in union density and CBAs coverage, level of centralisation, or degree of coordination—differences in another dimension can result in an entirely different bargaining system.

For example, the 2019 report by OECD and the subsequent academic paper by one of its co-author provide 5 distinct collective bargaining systems across the OECD countries according to the level of centralisation and the degree of wage coordination in collective bargaining:

Rather centralised and weakly coordinated (RCW) system

Predominantly centralised and coordinated (PCC) system

Organised decentralised and coordinated (ODC) system

Largely decentralised system (LD) system

Fully decentralised system (FD) system

Based on this, however, we can further simplify it into three predominant models of collective bargaining:

Decentralised system (i.e. FD + LD): collective bargaining primarily takes place at the firm- or enterprise-level and there is little to no coordination in collective bargaining between firms and sectors. Furthermore, because collective bargaining depends on having a union at the enterprise-level, CBAs coverage follows the level of unionisation in the economy. Consequently, countries with this system tend to have low CBAs coverage and union density. Most countries (particularly Anglo-countries like the US, UK, New Zealand, Canada, and Australia) use this system and thus represents the “typical” collective bargaining system. However, despite predominantly having firm-level bargaining, countries with a largely decentralised (LD) system such as in Australia, Greece, and Japan, have a limited form of sectoral bargaining for certain industries.

Centralised and weakly coordinated system (i.e. RCW): a strong role of sectoral or national-level collective bargaining but with relatively weak coordination in collective bargaining between firms or sectors. Because of this, lower-level CBAs often have limited flexibility to deviate from higher-level agreements and sectoral agreements often take a limited consideration of collective agreements in some sectors. Moreover, countries with this system tend to have a low union density but extensively use mandatory extension of higher-level collective agreements to ensure a high coverage of CBAs. An example of countries with this system is France, Italy, Iceland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland.

Centralised and highly coordinated system (i.e. PCC + ODC): under this system, collective bargaining predominantly occurs at the sectoral (ODC) or national level (PCC) but there is a strong role of coordination in collective bargaining between firms and sectors. As a result, centralised or sectoral bargaining often takes into account collective bargaining in some sectors as guidelines or benchmarks. Furthermore, this system often provides more flexibility for lower-level collective agreements to deviate from higher-level agreements, enabling unions to better adjust and coordinate their collective bargaining according to firm- or sector-specific conditions. This system is also characterised by a relatively high union density and CBAs coverage, particularly due to the use of CBA extension. Countries using this system include Finland, Belgium, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Why collective bargaining systems matters

These distinct collective bargaining systems are important not just because they represent the degree of power that labour union movements command over the economy. As shown in the paper by Andrea Garnero (one of the co-author of the 2019 OECD report), “The impact of collective bargaining on employment and wage inequality: Evidence from a new taxonomy of bargaining systems,” how collective bargaining institutions are organised matter because they can also result in significant differences in labour market outcomes.

First, wage inequality tends to be lower under centralised and coordinated collective bargaining systems compared under decentralised systems. The wage compression under centralised and coordinated systems occurs mainly between the workers at the bottom (decile 1) and top (decile 9) of the distribution. Put simply, centralised and coordinated systems are able to more effectively reduce wage inequality between the lowest and highest paid workers compared to decentralised systems (Table 2).

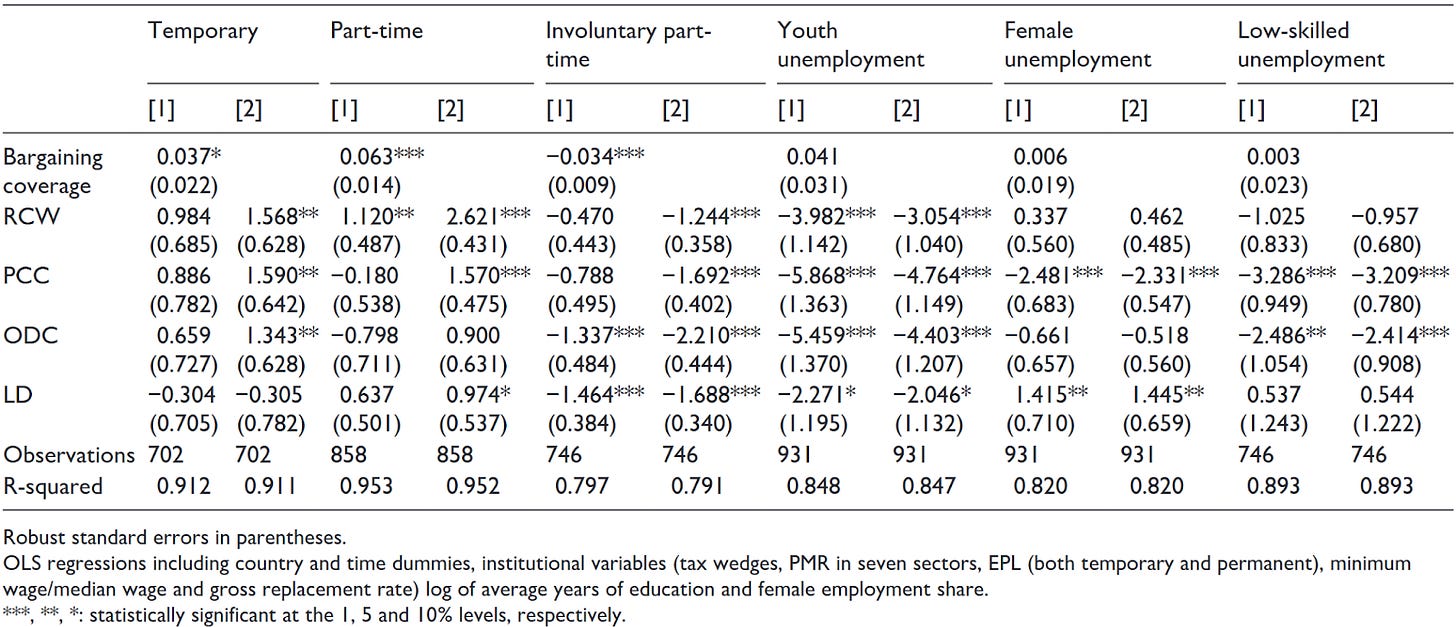

Second, countries with more centralised and coordinated bargaining systems tend to have higher employment rate and lower unemployment rate compared to decentralised systems (Table 3). Moreover, although centralised and coordinated systems tend to have higher rates of temporary and part-time employment, they are also associated with lower involuntary part time employment (see Table 4). However, centralised but less coordinated systems (RCW) are shown to be less effective at reducing involuntary part-time employment even compared to largely decentralised systems (LD) with limited sectoral bargaining.

Lastly, the labour market under centralised and coordinated systems tends to be more inclusive for more vulnerable demographics of workers. This can be seen in terms of lower unemployment rate for youth, women, and low-skilled workers under centralised and coordinated systems than under decentralised systems, and the effect is much stronger for highly coordinated systems (Table 4). Nevertheless, centralised but less coordinated systems (RCW) are shown as less inclusive for women workers, as shown by higher female unemployment rate compared to fully decentralised systems although smaller than under largely decentralised systems.

Based on his findings, Garnero argues for the importance of centralised and coordinated collective bargaining systems—whether predominantly centralised at the national or organised decentralised at the sectoral level—in promoting a better and more inclusive labour market compared to decentralised systems. Meanwhile, centralised but less coordinated systems are an intermediate position because, while they perform similarly or worse than decentralised systems in certain aspects such as for women and low-skilled unemployment rate, they share some similar positive labour market outcomes as centralised and highly coordinated systems. He concludes that:

“Coordinated bargaining systems are associated with higher employment, a better integration of vulnerable groups and lower wage inequality than fully decentralized systems…Strong coordination of wage targets, such as can be found in the Nordic countries, Germany or Belgium, is associated with better employment outcomes and lower wage inequalities. By ensuring that collective agreements take into account their macroeconomic effects, wage coordination safeguards the external competitiveness of the country, allows adaptation to the state of the business cycle and ensures similar wage increases across the whole economy.” (pp. 196-197)

Conclusion

In this blogpost, I show that the typical decentralised collective bargaining systems—where collective bargaining is predominantly done at the level of a single firm or enterprise, dependent on establishment of firm-level unions, and with CBAs only cover workers in the unionised firm—are not the only way to do collective bargaining. Some countries have different collective bargaining systems based on varying dimensions of CBAs and union membership coverage, level of centralisation, and degree of wage coordination. In some countries, such as in the Nordics or Continental Europe, CBAs coverage and union density is relatively high, collective bargaining is centralised at the sectoral or national-level, and there is a strong wage coordination between different bargaining units.

The different collective bargaining systems also have significant implications to the performance and inclusiveness of the labour market. Some studies have shown that centralised and coordinated collective bargaining systems tend to be associated with higher employment, lower wage inequality, and a more inclusive labour market for vulnerable demographics such as women, youth, and low-skilled workers compared to the typical decentralised systems. The mechanism seems to be that, under centralised and coordinated systems, vertically- and horizontally-integrated labour union organisations have shifted their collective bargaining strategies from merely winning gains for their respective union members towards macroeconomic governance in pursuing the goals of full employment and wage compression that benefits broader constituencies of workers—even non-unionised, vulnerable, and lower paid workers. Consequently, for countries with predominantly decentralised firm-level bargaining, building a more inclusive labour market might require a gradual shift towards centralised bargaining at the sectoral or national-level.

However, it is important to highlight that there is no “one size fits all” policy strategy. Ensuring that collective bargaining results in higher employment and lower wage inequality might require a more fine-grained approach to labour market reforms while at the same time developing strong integration and coordination between unions in the bargaining processes. Nonetheless, a shift from a decentralised system towards a more centralised and coordinated bargaining system would certainly transform labour union organisations from merely exercising their “protective” functions or advancing the interests of their respective members into an instrument by which labour unions and the whole labouring class can directly exercise control over macroeconomic governance for the benefit of all.

For more country-specific case study of collective bargaining institutions, especially with regards to minimum wage-setting, and including cases from the developing economies, see Simon Jäger, Suresh Naidu, and Benjamin Schoefer, “Collective Bargaining, Unions, and the Wage Structure: An International Perspective,” NBER Working Paper No. 33267 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2024); Maarten van Klaveren, Denis Gregory, and Thorsten Schulten, Minimum Wages, Collective Bargaining and Economic Development in Asia and Europe A Labour Perspective (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015); Irene Dingeldey, Damian Grimshaw and Thorsten Schulten, Minimum Wage Regimes: Statutory Regulation, Collective Bargaining and Adequate Levels (London: Routledge, 2021).

OECD, Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2019), pp. 54-56; see also Jäger et al, “Collective Bargaining,” pp. 7.

OECD, Navigating Our Way Up, pp. 57-59; Jäger et al, “Collective Bargaining,” pp. 11.

OECD, Navigating Our Way Up, pp. 49-50; Jäger et al, “Collective Bargaining,” pp. 8.

OECD, Navigating Our Way Up, pp. 61-62; see also Andrea Garnero, “The impact of collective bargaining on employment and wage inequality: Evidence from a new taxonomy of bargaining systems,” European Journal of Industrial Relations Vol. 27 No. 2 (2021): 185–202.

For a historical research of how organised labour gradually shifted their strategies from merely advancing the interests of their respective unions members towards macroeconomic management that can benefit broader constituencies of workers, see Erik Bengtsson, “The Origins of the Swedish Wage Bargaining Model,” International Labor and Working-Class History, Volume 103 (2023), pp. 162-178.